Update 2019-11-11: It has been a good while since I have updated this page, but my site is also getting a bit more traffic. I would suggest if you’re interested, check out my publications, Queen Quest, or twitter for more current stuff. I will update this…eventually.

I am broadly interested in pollinator and pollination ecology, conservation genetics, movement ecology, and fire ecology. In my research, I attempt to combine elements of all of these areas.

Bumble Bee Movement

See our publication on bumble bee movement tracking methods here:

Mola, J.M. and N. M. Williams. 2019. A review of methods for the study of bumble bee movement. Apidologie https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00662-3 [PDF]

Knowing the scales at which organisms operate throughout their life is a critical component to ecological research and species conservation. After all, a valuable habitat that is wholly inaccessible to an individual, directly or indirectly, does not impact its fitness.

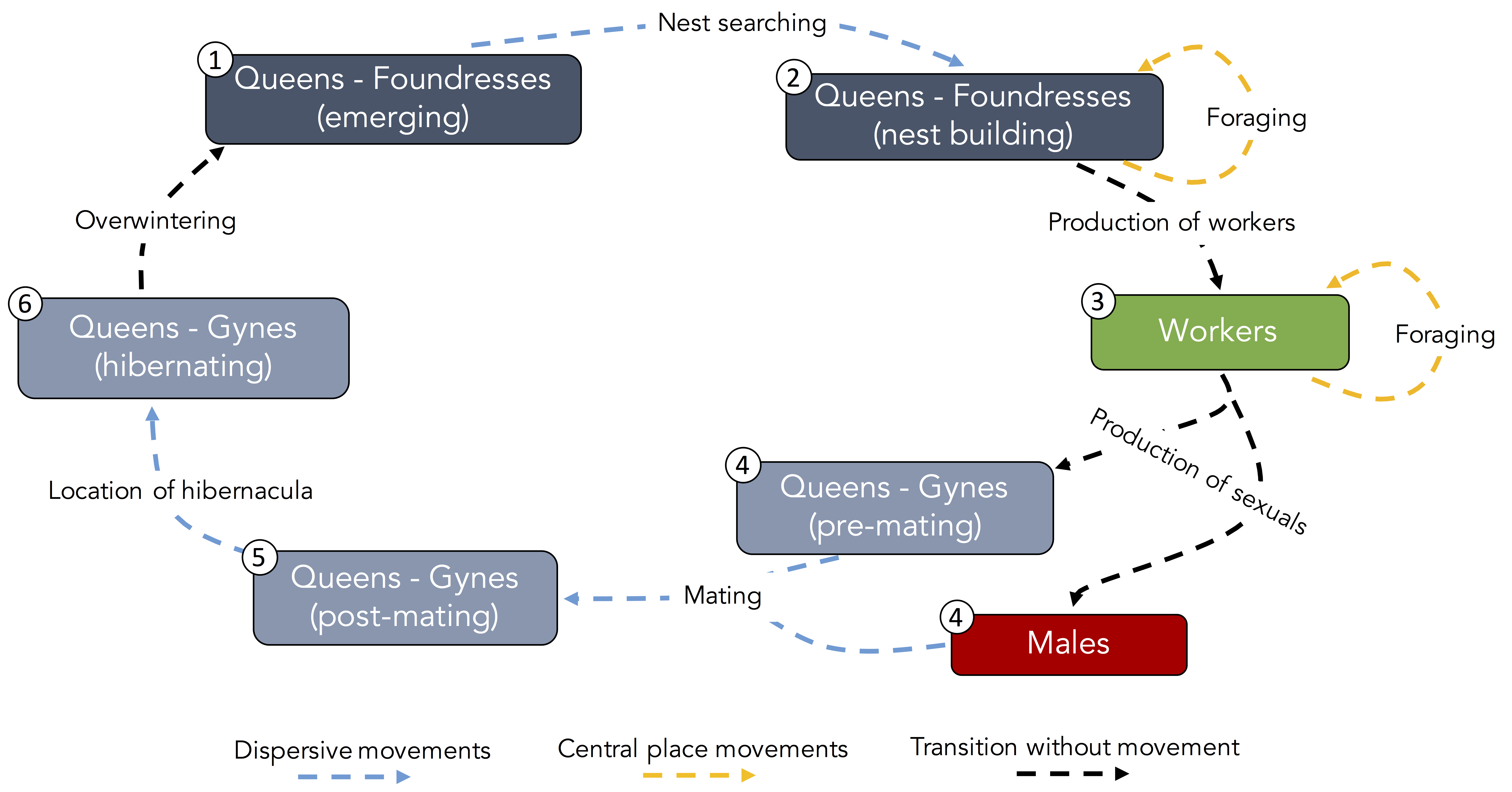

Figure 1: A typical bumble bee life cycle with the different movement phases labeled.

Figure 1: A typical bumble bee life cycle with the different movement phases labeled.

For bumble bees in particular, their movement patterns change with life stage, caste, behavioral phases, and response to landscape pattern. Research interest in their movement dates back at least to Darwin, but much is still to be learned. It is especially important to understand their movement ecology as mobile agents who pollination many of the world’s wild and crop plants.

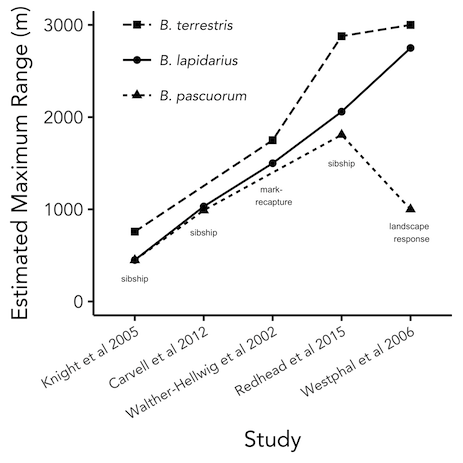

The bumble bee life cycle consists of several distinct phases and opportunities for movement (Figure 1). Yet, for most components, little is known about when, why, and how far individuals move. For instance, we have some crude estimates of worker foraging distance for several species, but the scale of movement for queens and males is relatively unknown. Further, what we do know is often complicated by differences in methodology, study region, and even in how researchers use terminology (Figure 2).

Bees, flowers, and fire

More information coming eventually… However, here are some publications I have authored on the subject:

-

Mola, J. M., and N. M. Williams. 2018. Fire-induced change in floral abundance, density, and phenology benefits bumble bee foragers. Ecosphere 9.

-

LoPresti, E. F., J. I. V. Wyk, J. M. Mola, K. Toll, T. J. Miller, and N. M. Williams. 2018. Effects of wildfire on floral display size and pollinator community reduce outcrossing rate in a plant with a mixed mating system. American Journal of Botany 105:1154–1164.

-

Mola, J. M., J. M. Varner, E. S. Jules, and T. Spector. 2014. Altered Community Flammability in Florida’s Apalachicola Ravines and Implications for the Persistence of the Endangered Conifer Torreya taxifolia. PLoS ONE 9:e103933.

-

Kreye, J. K., J. M. Varner, J. K. Hiers, and J. Mola. 2013. Toward a mechanism for eastern North American forest mesophication: differential litter drying across 17 species. Ecological Applications 23:1976–1986.