Our new paper looking at changes in bumble bee colony abundance, body size, and foraging and dispersal distance in out in Journal of Animal Ecology! Below, I provide some meandering background on the study, discuss a few key findings, and offer some musings on where I think research on bees and disturbance needs to go next.

Mola J.M., M.R. Miller, S. O’Rourke and N.M. Williams. 2020. Wildfire reveals transient change to individual traits and population responses of a native bumble bee Bombus vosnesenskii. Journal of Animal Ecology, Early View Online PDF

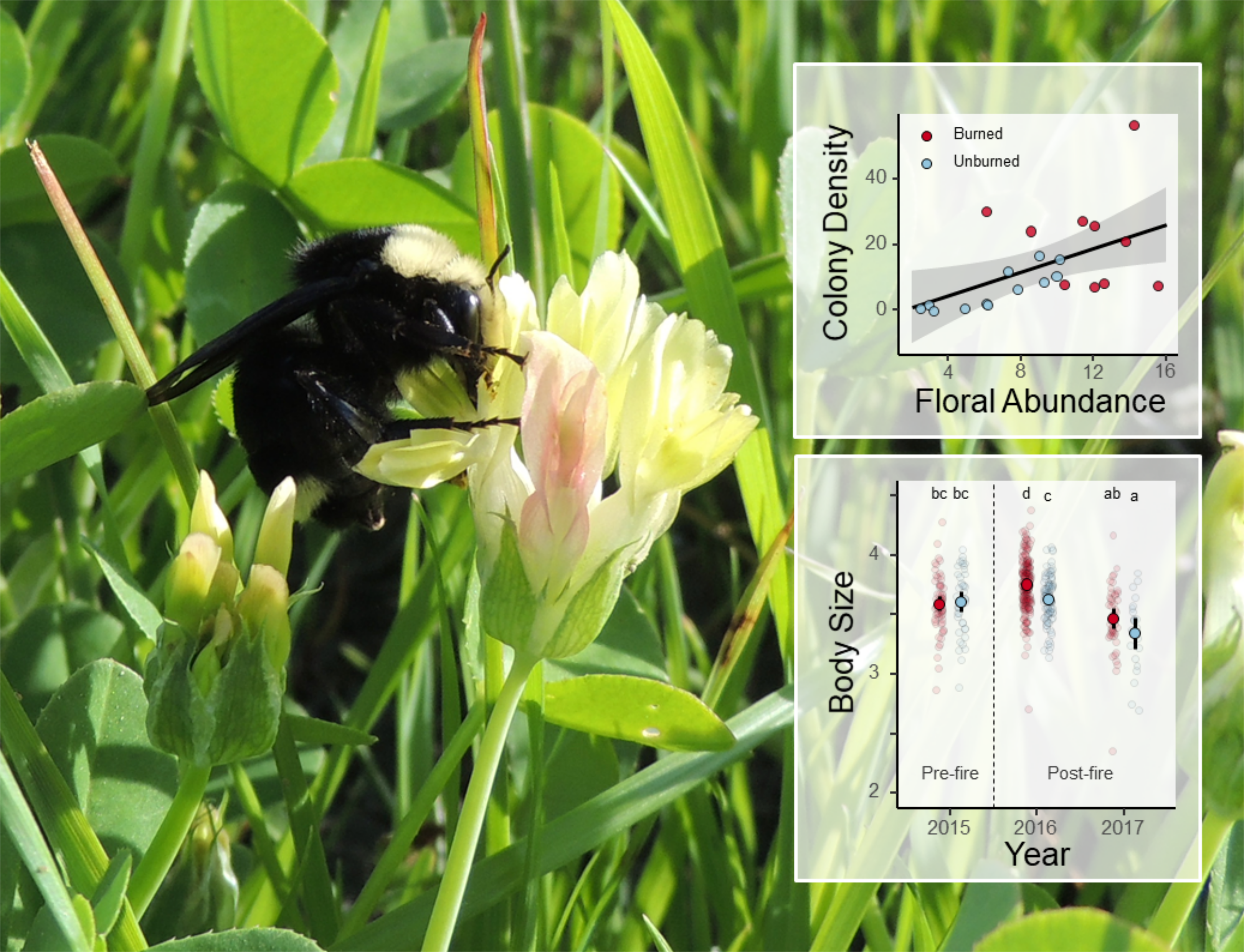

Graphical abstract: Bombus vosnesenskii queen on Trifolium fucatum with some key figures showing higher colony abundance and increased body sizes

Graphical abstract: Bombus vosnesenskii queen on Trifolium fucatum with some key figures showing higher colony abundance and increased body sizes

The effects of fire on plants has long been an interest of mine (see my first two publications!) - I found it fascinating that despite being raised to think fire = bad (Thanks, Smokey!), disturbance could actually be a driving force of biodiversity, habitat structure, and ecosystem health.

Despite being actively discouraged from pursuing the effects of fire on plants and pollinators when interviewing for master’s programs in 2011 (once even by someone who went on to publish work on the very topic…), the ideas always lingered in the back of my head.

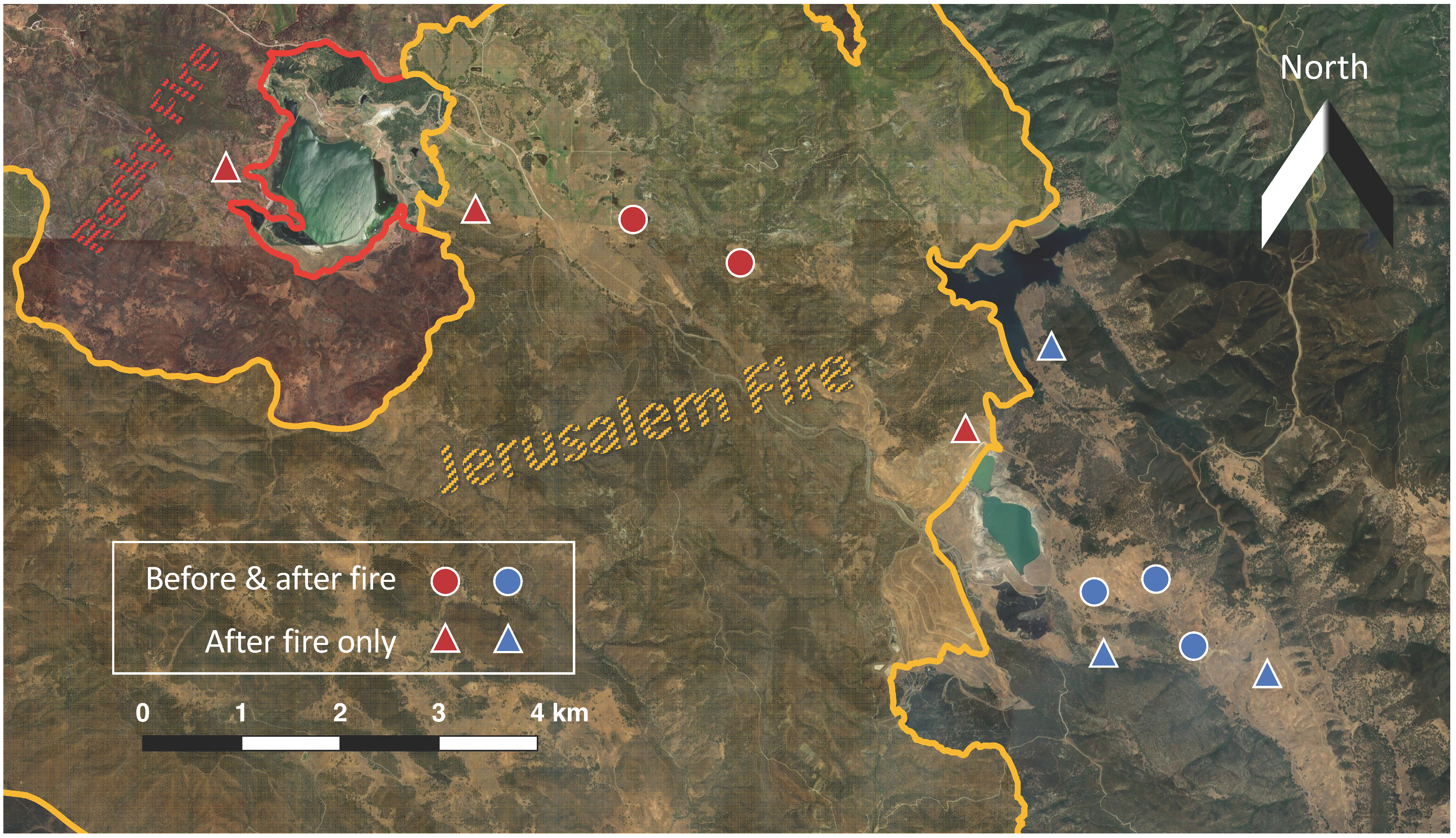

Slightly discouraged, I put thoughts on fire ecology aside for the moment. In 2015 I conducted the first field season of my PhD at the University of California McLaughlin Reserve. It was a pilot season. I hoped to collect enough genetic samples from bumble bee workers to get some estimates of colony abundance, foraging distance (by knowing the distances between individuals from the same colony), and just work out the kinks of the field and molecular methods.

As fate would have it, the field season was capped off with an arson fire burning through half of the reserve.

I guess I was studying fire after all!

Map showing the fires that burned through the reserve and my field sites

Map showing the fires that burned through the reserve and my field sites

Now, I can’t say that this was the ideal situation to study under. I didn’t know the sites were going to burn. In retrospect, if I had, I would have had like…40 more sites, a couple research assistants, more samples, and probably more money and a more reliable field vehicle. But, I think most PhD projects are a mix of pride and regret. In any event, I set out the next two years to learn about bumble bees and plants might be impacted by the fire.

We first learned something that we expected from the literature and past experience - a dizzying abundance of beautiful flowers in the burned area the first year after fire!

Cassie basking in the abundance blooms at a burned site

Cassie basking in the abundance blooms at a burned site

We found that these blooms resulted in a prolonged flowering seaso (although we do not know if it was because individual plants flowered longer or simply by there being a larger population the tails are “fatter”) and bumble bees were really abundant on the flowers. What we didn’t know, was if those bumble bees were from a lot of different colonies, or from a few lucky surviving lineages.

In the most recent work, we took advantage of the fact that we had genetic data and body size measurements from before and after fire. One common question in pollinator ecology is whether populations are floral resource limited (read Roulston and Goodell 2011 if you want a great review). I felt that by having these measurements available before fire, we would be able to see if the bumble bee population (not just the number of foragers) grew after fire in response to the abundant blooms. Additionally, we would be able to determine if body sizes became larger (suggesting more resources per colony) or if they decreased (more colonies establishing, but fewer resources per colony).

What we ended up finding was basically good news all around for bumble bees. We found more foragers, from more colonies. They had bigger body sizes, which is correlated with colony success (Herrmann et al. 2018), and there were more queens in the landscape than we had previously detected - and more than anyone else recalled from memory. Take a look at our figures if you please.

But I still think there’s a lot we don’t know. We don’t know whether the higher colony abundance is from queens dispersing into the landscape from outside the fire perimeter, or if through survival of queens in unburned patches. We don’t know exactly what these results mean for rare species or for management of endangered species (like the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee that I now work on).

I do think this work adds to a growing body of recent work showing how fire positively impacts bumble bee populations and the plants they rely on. For example, Mike Simanonok recently published some interesting work on how different fire severities result in different nutritional landscapes (Simanonok and Burkle 2019). And Sara Galbraith has done a great job looking at the response of bee communities broadly to the Douglas Fire complex in Oregon, showing that bumble bees became more abundant at higher burn severities (Galbraith et al. 2019).

I think targetted studies on how to manage bumble bee populations with fire are certainly warranted…and there’s a bunch of stuff I didn’t mention in this blog post. But perhaps what I find most interesting now are the questions beyond the fire->plants->bees pathway. Fire changes all sorts of aspects of environments that might be relevant for bees beyond floral abundance.

How might changes in soil moisture or bare ground following fire affect the nesting opportunities for bees? How might changed surface albedo in burned areas affect the surface temperatures of flowers and the behavior of visitors? How does fire and the more xeric environment following fire affect disease dynamics? How does smoke during a fire event affect foraging and insect navigation?

I think these questions are worth pursuing. Not just because fire is cool - but because they are opportunities to use fire events as a way to reveal something broader about ecological processes.

And that’s kinda neat.